Many of my younger patients, particularly those interested in facial aesthetics, have asked me about mewing. This practice, named after British orthodontist Dr. John Mew, involves specific tongue posture meant to reshape the jawline, improve breathing, and potentially correct misaligned teeth. The core idea is that the natural resting position of the tongue dictates the development of the face and jaws, and consciously correcting a “wrong” resting position can create positive structural changes.

While the principles of optimal oral posture are medically valid, the claims surrounding dramatic, rapid, and adult facial reshaping are often overstated online. I want to provide a clear, medically accurate perspective on the technique itself, its realistic benefits for health, and why expecting major changes as an adult is usually unrealistic.

What is Mewing and How Does it Affect the Skull?

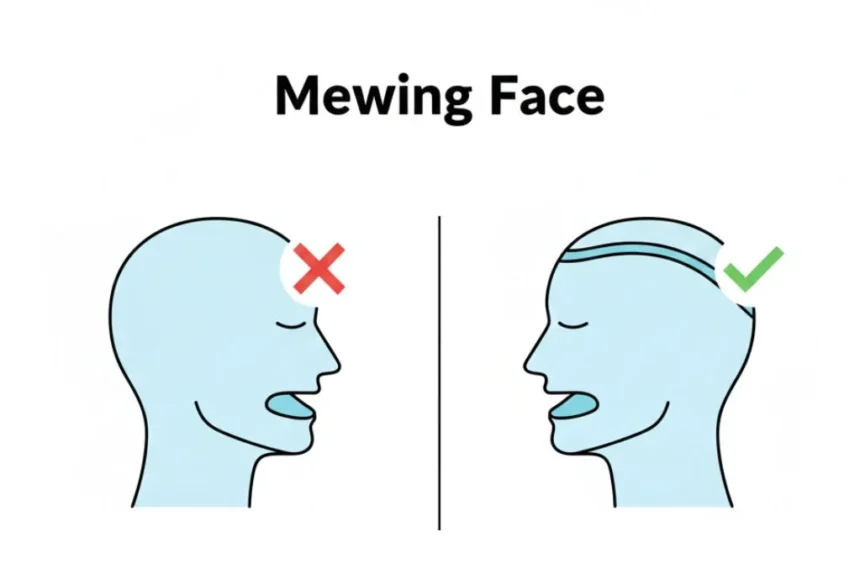

Mewing is the practice of maintaining the entire tongue flat against the roof of the mouth (the hard palate) while the lips are sealed and the teeth are lightly touching.

- Mechanism: The concept is rooted in Orthotropics, an orthodontic philosophy suggesting facial growth direction can be guided by muscle function and posture, particularly during childhood development. The constant, gentle pressure of the tongue is believed to widen the maxilla (upper jaw).

- Affect on the Skull: The maxilla is the foundational bone of the midface. The idea is that placing the tongue correctly provides outward and forward pressure, encouraging the face to grow in a more “forward” direction, potentially leading to a stronger jawline and better cheekbone prominence.

- Medical Reality (Childhood vs. Adulthood): This postural pressure is most effective during periods of active bone growth, primarily in children and adolescents. Once bone sutures have fused in adulthood (usually around ages 18-25), significant structural changes from simple tongue pressure are highly unlikely. Mewing acts on the skeleton only when the skeleton is still malleable.

Core Claims and Potential Health Benefits

While the aesthetic claims are often exaggerated, there are tangible health benefits associated with correct tongue posture.

- Improved Breathing: Correct tongue posture naturally opens the airway and encourages nasal breathing over mouth breathing. Mouth breathing, especially at night, is linked to poor sleep quality, dry mouth, and chronic dental problems.

- Better Jaw Alignment: Maintaining the tongue up and forward helps stabilize the jaw joint (temporomandibular joint, or TMJ). This can sometimes help relieve minor muscle tension or jaw pain related to a poor resting posture.

- Tonsil/Adenoid Relief: By expanding the upper palate, some practitioners theorize that correct tongue posture can contribute to improved space in the throat, potentially benefiting individuals prone to recurrent tonsillitis or obstructive sleep symptoms.

- Clinical Insight: I see many patients who are habitual mouth breathers. Merely getting them to consciously breathe through their nose and seal their lips during the day, which is the first step of mewing, dramatically reduces their morning dry mouth and improves their energy levels due to better nocturnal oxygen intake.

Actual Technique: A Step by Step Guide

Mewing is a constant state, not an exercise. It should feel effortless and become the default resting position.

- Seal the Lips: Close your lips naturally without straining.

- Lightly Touch Teeth: Your back teeth should be lightly touching or very close, but not clenched.

- Find the “Suction Spot”: Say the word “SING.” Notice where the back of your tongue touches the roof of your mouth to make the “NG” sound. This is the spot you want to engage.

- Engage the Back Third: Press the entire tongue flat against the hard palate, making sure the crucial back third of the tongue is pressed up, not drooping down toward the throat. You should feel tension under the chin and along the jaw.

- Swallowing Practice: Practice swallowing while maintaining this posture. The tongue should move in a wave motion against the palate, pushing the food/liquid backward, rather than the face muscles clenching outward.

Common Errors in Practice

| Incorrect Practice | Correct Practice |

| Pushing only the tip of the tongue forward | Engaging the entire tongue, especially the back third |

| Clenching the teeth tightly | Allowing the teeth to lightly touch or remain slightly apart |

| Straining muscles under the chin | Finding a relaxed, suction-like resting state |

Practical Risks and Side Effects

While the technique itself is non-invasive, excessive force or improper technique can lead to unwanted side effects.

- TMJ Strain/Pain: Excessively clenching the teeth while attempting to mew, or pressing too hard with the tongue, can put undue stress on the jaw joints, leading to pain, clicking, or headaches.

- Teeth Misalignment: Attempting to use the tongue to forcefully shift teeth without orthodontic guidance can, in theory, push teeth into incorrect positions. The pressure should be light and constant, not forceful.

- Oral Fatigue: When first starting, the muscles of the tongue and the area under the chin may feel sore or tired. This is normal and should subside as the posture becomes automatic.

Mewing vs. Orthodontics: When to Seek Professional Help

Mewing is a postural self-correction tool; it is not a substitute for professional medical or dental treatment.

- Postural Guidance: If you have mild facial asymmetry, poor resting posture, or chronic mouth breathing, mewing may complement other therapies.

- Structural Correction: If you have a severe malocclusion (bad bite), severe crowding, an overbite, or persistent TMJ pain, mewing alone will not fix the problem. You need professional intervention.

- Professionals to Consult:

- Orthodontist: For teeth and jaw alignment issues.

- Oral Myofunctional Therapist: A specialist trained to address tongue posture, swallowing patterns, and oral rest positions. This is the most appropriate professional to guide mewing safely.

When to See a Doctor

If you experience any of the following, stop the practice and consult a specialist:

- Persistent Jaw Pain: Jaw pain, locking, or clicking that worsens after starting mewing.

- Tooth Pain or Shifting: Any noticeable or painful movement of teeth.

- Breathing Difficulties: Worsening symptoms of sleep apnea or habitual mouth breathing, indicating the technique may be incorrect or inadequate.

Improvement Timeline

Visible results from changes in tongue posture are extremely slow and dependent on age and consistency.

| Time Frame | Expected Change | Rationale |

| Days 1-7 | Muscle fatigue, increased awareness of tongue position. | Conscious effort is tiring; neural pathways are establishing. |

| Weeks 3-4 | Posture becomes the default when not speaking; improved nasal breathing. | Muscle memory is starting to form; functional benefits appear first. |

| 6 Months + | Subtle aesthetic changes (only if bone growth is ongoing) or significant reduction in jaw tension. | Structural change is very slow; most adults only achieve functional relief. |

Final Advice

The true value of mewing is promoting better oral rest posture and encouraging nasal breathing, which are fundamentally important for long term health. Do not view it as a shortcut to plastic surgery. If you are an adult, focus on the functional benefits: better sleep, reduced jaw tension, and improved respiratory health. If you are practicing with a child, always do so under the supervision of a qualified dentist or orthodontist to ensure their development is on the right track.

Medical Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It is not a substitute for professional medical care. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare provider, orthodontist, or oral myofunctional therapist with any questions you may have regarding jaw pain, facial development, or oral posture.

References

- Mew, J. R. (2012). The relationship between posture and malocclusion: A review. The Journal of Orthodontics.

- Huang, S., et al. (2018). Orthodontic treatment and facial aesthetic changes. Orthodontics & Craniofacial Research.

- Harvold, E. P., et al. (1981). Primate experiments on oral respiration. American Journal of Orthodontics.

- Lopes, T. S., et al. (2019). The relationship between tongue position and mandibular growth. International Orthodontics.

- American Association of Orthodontists (AAO). (2020). Guidelines on the management of sleep disordered breathing.

- Proffit, W. R., Fields, H. W., & Larson, B. E. (2019). Contemporary Orthodontics. Elsevier.

- Al-Aswad, Z. A. (2017). Effects of oral breathing on dental and facial development. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry.