After 15 years in clinical practice, I’ve reviewed thousands of complete blood counts. And I can tell you this: the MCV is one of the most overlooked yet incredibly valuable numbers on your lab report. Let me share what I’ve learned from years of diagnosing and treating patients based on this simple measurement.

What Is the MCV Blood Test and Why Should You Care?

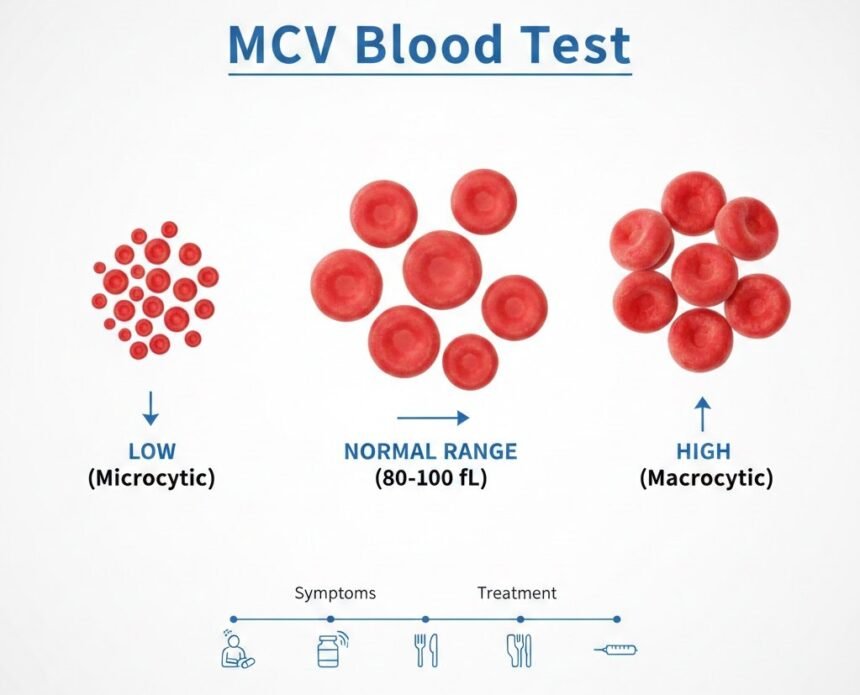

The Mean Corpuscular Volume measures the average size of your red blood cells in femtoliters. I explain it to patients this way: imagine your red blood cells are cars on a highway carrying oxygen to every tissue in your body. The MCV indicates whether those cars are compact, standard, or oversized.

This matters because the size of your red blood cells points directly to specific deficiencies, genetic conditions, or underlying diseases. In my experience, an abnormal MCV often leads us to diagnoses that patients and even some physicians might have missed otherwise.

Clinical Significance I See Every Day

Let me be direct about something most doctors know but don’t always communicate clearly: your MCV can reveal problems months or even years before you develop serious symptoms.

I once had a 45-year-old executive who came in for a routine physical, feeling perfectly fine. His MCV was 78 (normal is 80-100). Further workup revealed he was slowly bleeding from a small colon polyp. We caught it early, removed it, and potentially prevented colon cancer. He had zero symptoms, just a low number on a blood test.

That’s the power of understanding what MCV tells us.

Normal MCV Blood Test Values: What the Numbers Actually Mean

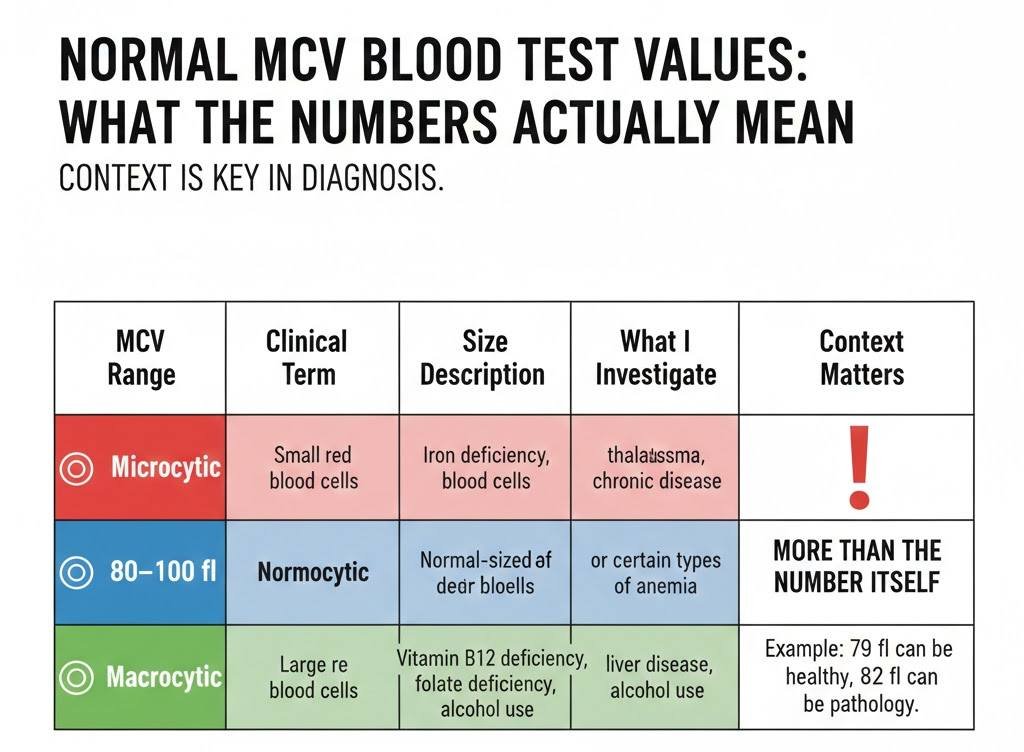

In my practice, I use these reference ranges:

| MCV Range | Clinical Term | Size Description | What I Investigate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Below 80 fL | Microcytic | Small red blood cells | Iron deficiency, thalassemia, chronic disease |

| 80–100 fL | Normocytic | Normal-sized red blood cells | Usually healthy, or certain types of anemia |

| Above 100 fL | Macrocytic | Large red blood cells | Vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, liver disease, alcohol use |

But here’s what medical school doesn’t always teach you: context matters more than the number itself. I’ve seen patients with an MCV of 79 who are perfectly healthy, and others with an MCV of 82 who have significant pathology.

Low MCV: My Diagnostic Approach to Microcytic Anemia

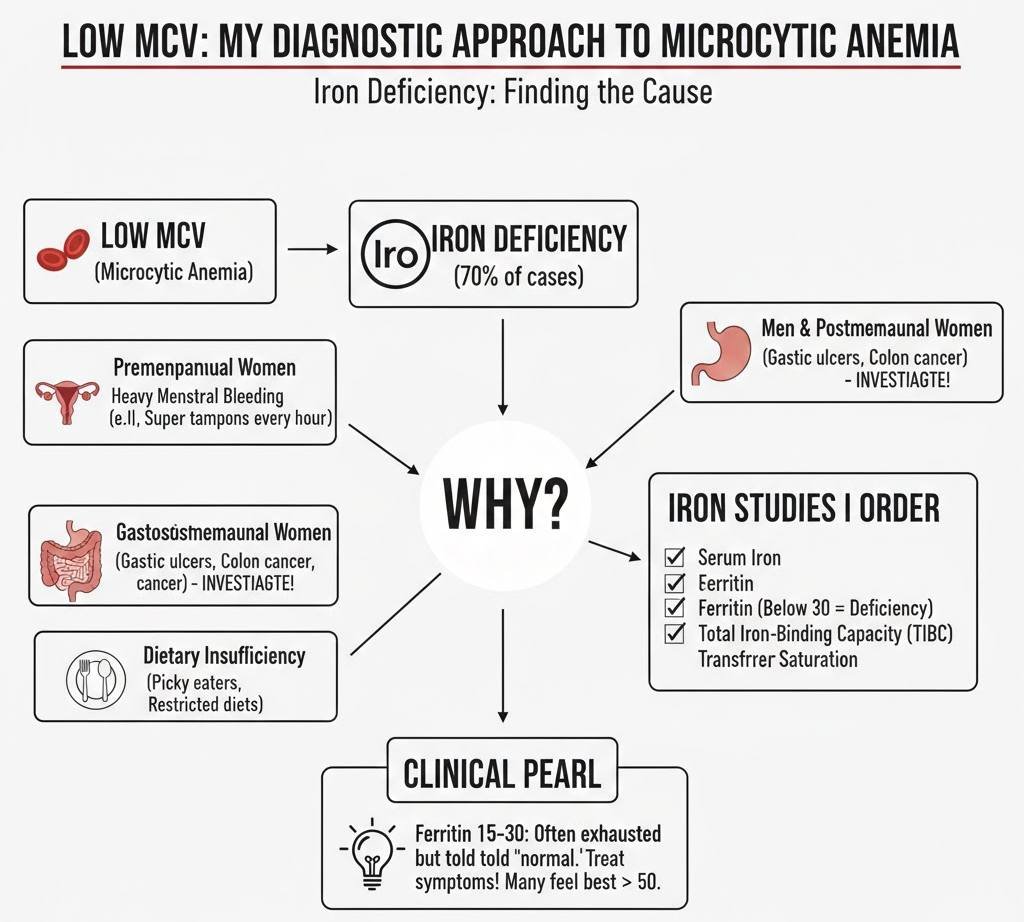

When I see a low MCV, my mind immediately goes through a diagnostic algorithm I’ve refined over years of practice.

Iron Deficiency: The Most Common Culprit

Approximately 70% of low MCV cases in my practice are due to iron deficiency. But finding iron deficiency is just the beginning. The real question is: why?

- In premenopausal women, I almost always ask about menstrual bleeding. Heavy periods are responsible for more iron deficiency than any other single cause in this population. I’ve had patients bleeding through super tampons every hour during their cycles who thought this was normal. It’s not.

- In men and postmenopausal women, iron deficiency is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding until proven otherwise. I’ve diagnosed everything from gastric ulcers to colon cancer this way. This is why I never prescribe iron and move on without investigating the source.

- In young children, dietary insufficiency is common, especially in picky eaters or those on restricted diets.

Iron Studies I Order

When MCV is low, I always order a complete iron panel:

- Serum iron: Often low in deficiency

- Ferritin: The single best test for iron stores. Below 30 ng/mL, I’m treating for deficiency. Below 15, I’m definitely investigating why.

- Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC): Elevated in iron deficiency

- Transferrin saturation: Below 20% suggests deficiency

One pattern I see repeatedly: patients with ferritin levels of 15-30 who feel exhausted but are told they’re “normal.” In my clinical experience, many people don’t feel their best until ferritin is above 50. I treat symptoms, not just numbers.

Thalassemia: The Genetic Condition That Mimics Iron Deficiency

This is where clinical experience really matters. Thalassemia and iron deficiency both cause low MCV, but their treatments are completely different.

Red flags that make me think thalassemia:

| Clinical Finding | What It Suggests / Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| MCV below 75 fL, but hemoglobin only mildly low (or even normal) | Strongly suggests thalassemia trait rather than iron deficiency anemia |

| Normal or high ferritin despite low MCV | Iron stores are adequate — points away from iron deficiency and toward thalassemia |

| Family history from Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, African, or Southeast Asian descent | Higher prevalence of thalassemia in these populations |

| Lack of response to iron supplementation | Supports thalassemia diagnosis instead of iron deficiency |

| MCV is disproportionately low compared to the degree of anemia | Classic feature of thalassemia trait (very small cells but mild anemia) |

I use the Mentzer index (MCV divided by RBC count). If it’s less than 13, I’m thinking thalassemia. If it’s more than 13, iron deficiency is more likely.

I had a young Greek woman who had been taking iron supplements for two years with no improvement. Her MCV was 72, hemoglobin 11.5, and ferritin 150. Hemoglobin electrophoresis confirmed beta-thalassemia trait. She stopped the unnecessary iron use, and we focused on monitoring rather than treating.

Anemia of Chronic Disease

Long-standing inflammation from conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or chronic kidney disease can cause a low or low-normal MCV.

The tricky part? These patients often also have true iron deficiency. I use additional markers, such as CRP, ESR, and, sometimes, hepcidin levels, to sort this out.

High MCV: My Systematic Approach to Macrocytic Anemia

An elevated MCV activates a different diagnostic pathway in my mind.

Vitamin B12 Deficiency: More Common Than You Think

I’ve diagnosed B12 deficiency in everyone from strict vegans to elderly patients with pernicious anemia. The presentation varies widely.

Classic symptoms I ask about:

| Symptom / Sign | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|

| Fatigue and weakness (present in almost everyone) | Common symptom of anemia due to reduced oxygen delivery to tissues |

| Numbness or tingling in hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy) | Suggests nerve involvement, commonly seen in Vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Difficulty with balance or walking | Indicates neurological impairment, often linked to prolonged B12 deficiency |

| Memory problems or confusion (can mimic dementia in elderly patients) | Neurological complication of B12 deficiency; may be reversible if treated early |

| Glossitis (smooth, red tongue) | Classic sign of Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency |

Important clinical pearl: Neurological symptoms from B12 deficiency can occur even before anemia develops. I’ve seen patients with normal MCV and hemoglobin but B12 levels of 150 pg/mL with significant neuropathy. This is why I sometimes check B12 even when MCV is normal if symptoms suggest it.

B12 Testing I Perform

| Test | How I Interpret It / Clinical Use |

|---|---|

| Serum B12 | I treat if below 300 pg/mL, especially if symptoms are present. Although the lab “normal” range may go as low as 200 pg/mL, deficiency symptoms can occur between 200–400 pg/mL. |

| Methylmalonic Acid (MMA) | Elevated in true Vitamin B12 deficiency. Particularly useful when B12 levels are borderline. |

| Homocysteine | Elevated in Vitamin B12 deficiency and also in folate deficiency. Helps support diagnosis when B12 is uncertain. |

| Intrinsic Factor Antibodies | Ordered when pernicious anemia is suspected. Positive result supports autoimmune B12 deficiency. |

Folate Deficiency: Less Common Now But Still Important

Since food fortification began, I see fewer cases of folate deficiency than of B12 deficiency, but it still happens.

High-risk groups in my practice:

| At-Risk Group | Why They Are at Risk (Clinical Reason) |

|---|---|

| Heavy alcohol users | Alcohol interferes with folate metabolism and absorption, increasing risk of folate deficiency |

| Pregnant women with inadequate prenatal care | Higher folate requirements during pregnancy; deficiency increases risk of anemia and neural tube defects |

| Patients on certain medications (methotrexate, trimethoprim, phenytoin) | These drugs interfere with folate metabolism or absorption |

| People with malabsorption disorders | Conditions like celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or post-GI surgery reduce folate absorption |

Critical point for pregnancy: I always ensure adequate folate before conception and during the first trimester. Neural tube defects develop in the first 28 days of pregnancy, often before women know they’re pregnant. This is why I recommend all women of childbearing age take 400-800 mcg of folic acid daily.

Alcohol and MCV: A Reliable Marker

In my experience, MCV is one of the most sensitive markers for chronic alcohol use. I see MCVs of 100-110 regularly in patients who drink heavily, even when liver function tests are still normal.

Here’s what’s interesting: the MCV can stay elevated for months after someone stops drinking. I use it to monitor recovery and abstinence. When a patient tells me they’ve quit drinking, but their MCV keeps rising, we need to have an honest conversation.

Hypothyroidism and MCV

An underactive thyroid can elevate MCV, though usually not dramatically. I typically see MCVs in the 95-105 range with hypothyroidism.

I always check TSH when I see unexplained macrocytosis. Many times I’ve discovered hypothyroidism this way, especially in women over 40.

Medication-Induced Macrocytosis

Several medications cause elevated MCV, and I need to know my patient’s medication list before I start an expensive workup.

Common offenders I see:

| Medication | Common Use | Why It Matters (Hematologic Effect) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyurea | Sickle cell disease, certain cancers | Can cause macrocytosis due to effects on bone marrow and DNA synthesis |

| Methotrexate | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, cancer | Interferes with folate metabolism, leading to macrocytosis |

| Azathioprine | Immune suppression (autoimmune disease, transplant) | Suppresses bone marrow, may cause macrocytosis |

| HIV medications (especially zidovudine) | HIV treatment | Commonly causes macrocytosis without anemia; affects DNA production |

| Chemotherapy agents | Cancer treatment | Suppress bone marrow and impair DNA synthesis, leading to macrocytosis |

| Valproic acid | Seizures, bipolar disorder | Can alter bone marrow function and cause macrocytosis |

If you’re on any of these medications, an elevated MCV doesn’t surprise me. I monitor it to ensure it stays stable, but I don’t usually need to treat it.

My Physical Examination Findings That Correlate With MCV

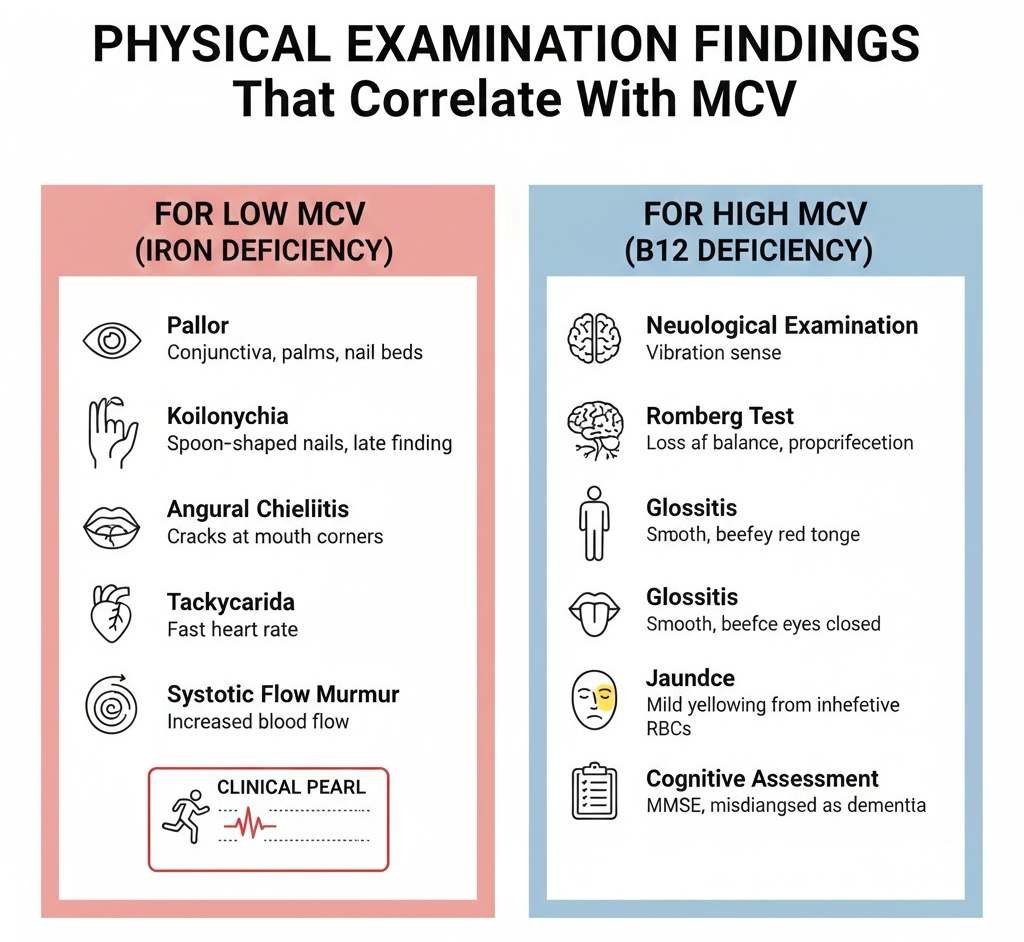

When I examine a patient with abnormal MCV, I’m looking for specific signs.

For Low MCV (Iron Deficiency)

- Pallor: I check the conjunctiva (the inner lining of the lower eyelid), the palms, and the nail beds. Pale pink or white suggests anemia.

- Koilonychia: Spoon-shaped nails that are concave instead of convex. This is a late finding, but very specific for iron deficiency.

- Angular cheilitis: Cracks at the corners of the mouth.

- Tachycardia: Fast heart rate as the body tries to compensate for low oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Systolic flow murmur: Caused by increased blood flow through the heart.

I had a marathon runner once who came to me because she couldn’t finish her long runs anymore. Her resting heart rate had gone from 55 to 85. Physical exam showed severe pallor and koilonychia. Her MCV was 68, ferritin 4. After four months of iron replacement, she qualified for Boston.

For High MCV (B12 Deficiency)

- Neurological examination: I check vibration sense, proprioception, and reflexes. B12 deficiency causes posterior column dysfunction.

- Romberg test: Patients with B12 deficiency often exhibit a positive Romberg sign (loss of balance with eyes closed).

- Glossitis: Smooth, beefy red tongue.

- Jaundice: Mild jaundice can occur from ineffective red blood cell production.

- Cognitive assessment: In severe cases, I administer the Mini-Mental State Exam. I’ve seen B12 deficiency misdiagnosed as dementia.

Additional Testing I Order

An abnormal MCV never stands alone. Here’s my typical workup.

For Low MCV

| Investigation / Test | Purpose / What It Helps Identify |

|---|---|

| Complete iron studies (serum iron, TIBC, ferritin, transferrin saturation) | Confirms iron deficiency and distinguishes it from other causes of anemia |

| Reticulocyte count | Shows whether the bone marrow is responding appropriately to anemia |

| Hemoglobin electrophoresis | Detects thalassemia and other hemoglobin disorders |

| Stool for occult blood | Screens for hidden gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy (in men and postmenopausal women) | Identifies gastrointestinal sources of chronic blood loss |

| Celiac panel (if iron deficiency does not respond to treatment) | Screens for celiac disease, which can impair iron absorption |

For High MCV

| Test / Investigation | Purpose / What It Helps Identify |

|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 level | Screens for B12 deficiency as a cause of macrocytic anemia |

| Folate level | Identifies folate deficiency |

| TSH (thyroid function test) | Detects hypothyroidism, which can cause macrocytosis |

| Liver function tests | Evaluates liver disease as a possible cause of macrocytosis |

| Reticulocyte count | Assesses bone marrow response and helps differentiate causes of anemia |

| If B12 is low: Methylmalonic acid (MMA) | Confirms true B12 deficiency (elevated in B12 deficiency) |

| If B12 is low: Homocysteine | Elevated in both B12 and folate deficiency |

| If B12 is low: Intrinsic factor antibodies | Evaluates for pernicious anemia (autoimmune B12 deficiency) |

| Peripheral blood smear | Identifies hypersegmented neutrophils, confirming megaloblastic anemia |

In certain cases: bone marrow biopsy (rare, but necessary if I suspect myelodysplastic syndrome or other bone marrow disorders)

Real Cases From My Practice That Changed My Approach

Case That Taught Me About Pernicious Anemia

A 68-year-old woman came to me with increasing confusion and difficulty walking. Her family thought she had Alzheimer’s. Her MCV was 115, and her B12 level was 120 pg/mL.

Testing revealed pernicious anemia with positive intrinsic factor antibodies. After starting B12 injections, her mental clarity returned within weeks. Her gait improved over the months. She had no dementia, just severe B12 deficiency affecting her brain and spinal cord.

This case taught me to always check B12 in elderly patients with cognitive changes before assuming dementia.

Young Woman With Heavy Periods

A 28-year-old woman had been tired for years. She thought everyone felt this exhausted. Her previous doctor said her labs were “a little low, but nothing to worry about.”

Her MCV was 76, hemoglobin 9.5, ferritin 8. She was soaking through a super-plus tampon every hour during her period. We treated her menorrhagia with hormonal therapy and started iron supplementation.

Six months later, her ferritin was 65, MCV 88, and hemoglobin 13.2. She told me, “I didn’t know life could feel this good. I thought I was just lazy.”

This case reinforced that “low-normal” isn’t always optimal. I treat the patient, not just the lab values.

Alcoholic Who Saved His Own Life

A 52-year-old man came for a work physical. He denied alcohol use. His MCV was 106, and liver enzymes were mildly elevated.

I explained that his MCV suggested significant alcohol consumption. He initially denied it, but eventually admitted to drinking a pint of vodka daily for ten years.

We connected him with addiction services. He got sober. One year later, his MCV was 94, and liver enzymes were normal. Five years later, he’s still sober and healthy.

His elevated MCV literally started the conversation that saved his life.

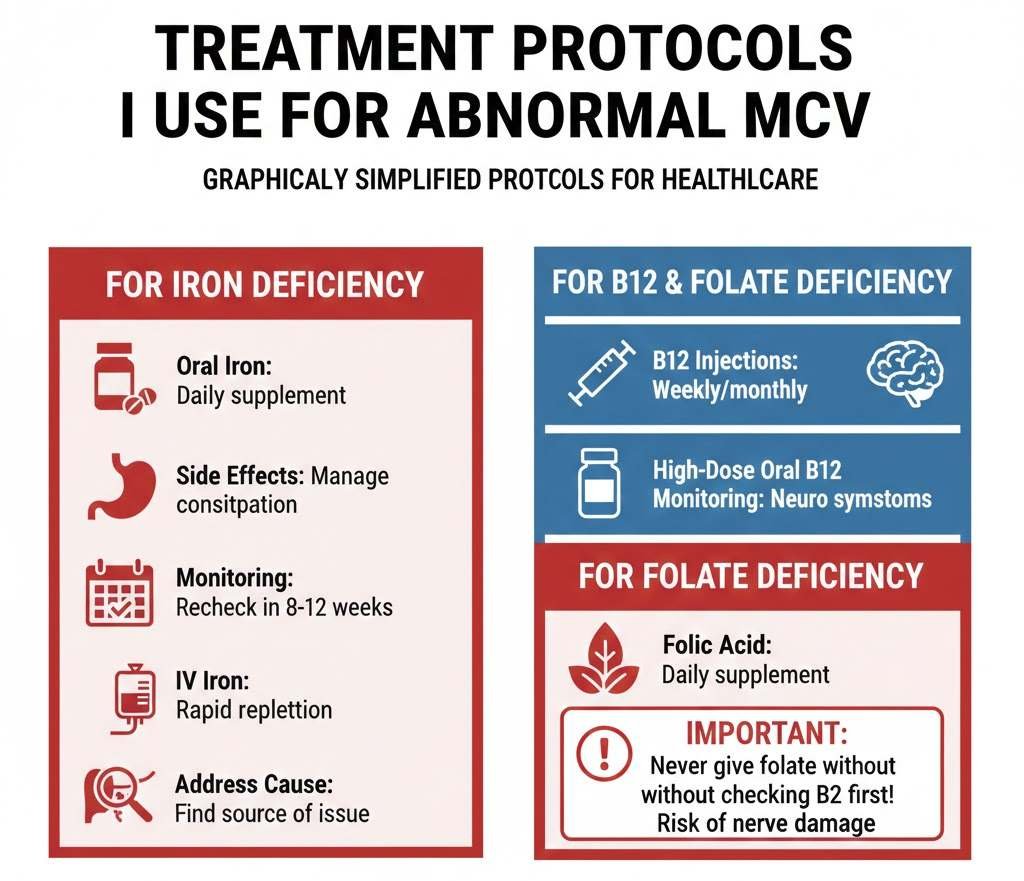

Treatment Protocols I Use

For Iron Deficiency

- Oral iron supplementation: I prescribe ferrous sulphate 325 mg (65 mg elemental iron) once or twice daily. I tell patients to take it on an empty stomach with vitamin C for better absorption.

- Side effects management: Constipation is common. I recommend stool softeners and starting with lower doses, then increasing as tolerated.

- Monitoring: I recheck complete blood count and ferritin in 8-12 weeks. MCV should start improving within 4-6 weeks, though it may take 3-6 months to normalise fully.

- IV iron: I use this for patients who can’t tolerate oral iron, have malabsorption, or need rapid repletion. It works much faster than oral iron.

- Address the underlying cause: This is critical. If I don’t stop the bleeding or fix the absorption problem, iron supplementation is just a temporary band-aid.

For B12 Deficiency

- Cyanocobalamin injections: For severe deficiency or pernicious anemia, I give 1000 mcg intramuscularly weekly for 4-8 weeks, then monthly for life.

- High-dose oral B12: For mild deficiency without pernicious anemia, I use 1000-2000 mcg daily. Despite malabsorption, this dose remains effective because it acts by passive diffusion.

- Sublingual B12: Some patients prefer this. It’s effective for most forms of deficiency except severe pernicious anemia.

- Monitoring: I recheck B12 and MCV in 8-12 weeks. Neurological symptoms can take 6-12 months to improve fully, and some nerve damage may be permanent if the deficiency persists.

For Folate Deficiency

- Folic acid supplementation: 1-5 mg daily, depending on severity and underlying cause.

- Important warning: I never give folate without checking B12 first. Giving folate to someone with B12 deficiency can improve their anemia, but worsen neurological damage. This is a crucial mistake to avoid.

MCV Blood Test in Special Populations: My Clinical Experience

Pregnancy

Normal pregnancy causes a slight decrease in MCV due to hemodilution (blood volume increases more than red blood cell mass). However, I take iron deficiency very seriously in pregnant women.

I check the complete blood count in the first trimester and again at 28 weeks. If MCV is low, I start iron supplementation immediately. Iron deficiency in pregnancy increases the risks of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and postpartum hemorrhage.

I recommend all pregnant women take prenatal vitamins containing at least 27 mg of iron and 400-800 mcg of folic acid.

Elderly Patients

I see a lot of B12 deficiency in my elderly patients. Absorption decreases with age due to decreased stomach acid production. Many are on proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole), which further impair B12 absorption.

I have a low threshold for checking B12 in patients over 65, especially those with cognitive changes, balance problems, or neuropathy. I’ve prevented misdiagnoses of dementia this way.

Athletes

Endurance athletes, particularly runners, have unique issues with MCV.

- Foot-strike hemolysis: Repetitive pounding destroys red blood cells, releasing hemoglobin that’s lost in urine.

- GI bleeding: Long-distance running causes microscopic bleeding in the intestines.

- Dilutional pseudoanemia: Training increases plasma volume faster than red blood cell production, temporarily lowering MCV and hemoglobin.

- Increased iron loss: Through sweat, the GI tract, and hemolysis.

- I’ve worked with several competitive runners. I check their iron stores (ferritin) every 3-6 months during heavy training. I aim for ferritin above 50 ng/mL for optimal performance.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Patients with advanced kidney disease develop anemia because their kidneys don’t produce enough erythropoietin, the hormone that stimulates red blood cell production.

Their MCV is usually normal or slightly low. I treat them with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and ensure adequate iron stores. Target hemoglobin is 10-11 g/dL (not higher, as studies showed increased cardiovascular risk with higher targets).

Cancer Patients

Chemotherapy commonly affects MCV. Many chemo drugs cause macrocytosis. I monitor complete blood count regularly during treatment.

Anemia in cancer patients has multiple causes: chemotherapy, bone marrow suppression, cancer invasion of bone marrow, bleeding, nutritional deficiencies, or chronic disease effects. MCV helps me narrow down the cause.

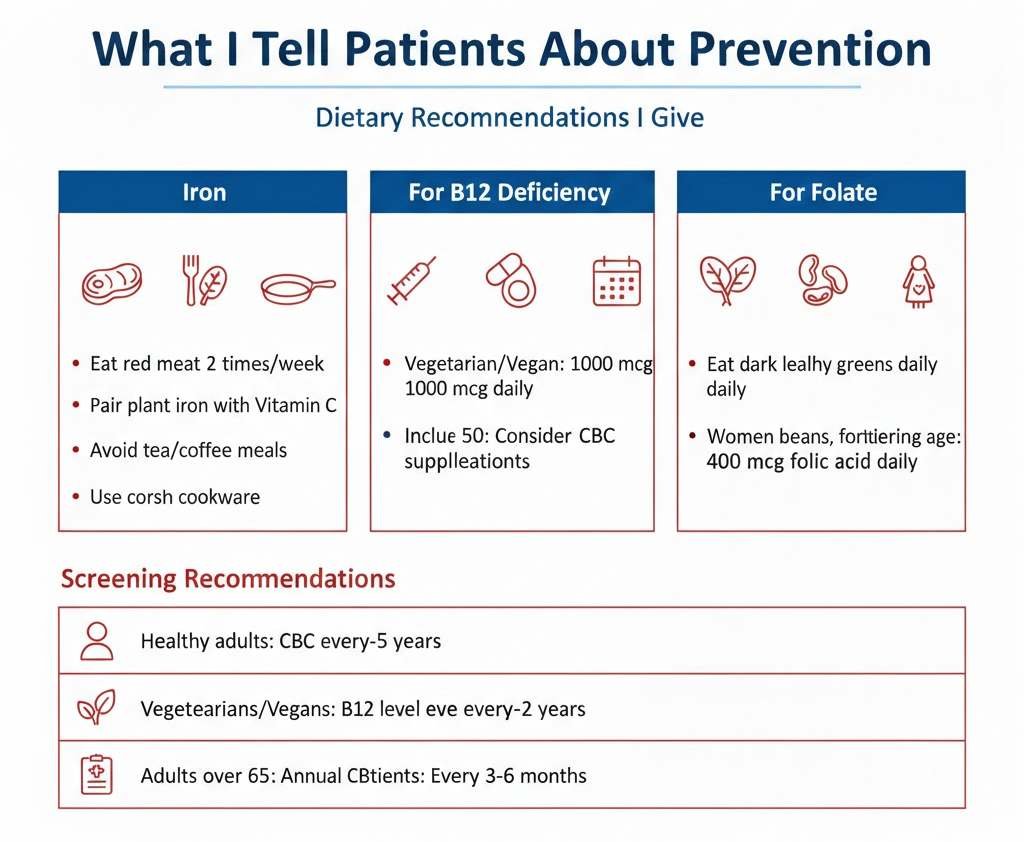

What I Tell Patients About Prevention

Prevention is always better than treatment. Here’s my advice for maintaining healthy red blood cells.

Dietary Recommendations I Give

- For iron: Eat red meat 2-3 times per week (the best source for iron absorption). Include chicken, fish, and eggs regularly. Pair plant-based iron sources (beans, lentils, spinach) with vitamin C. Avoid tea and coffee with meals (they inhibit iron absorption). Consider cast iron cookware (adds iron to food)

- For B12: If you’re vegetarian or vegan, take B12 supplements (1000 mcg daily). Include eggs and dairy if you’re vegetarian. Anyone over 50 should consider B12 supplementation due to decreased absorption.

- For folate: Eat dark leafy greens daily. Include beans, lentils, and fortified grains. Women of childbearing age should take 400 mcg of folic acid daily.

Screening Recommendations

- Healthy adults: Complete blood count every 2-5 years with routine physical

- Women with heavy periods: Annual CBC at minimum, more often if symptomatic

- Vegetarians and vegans: B12 level every 1-2 years

- Adults over 65: Annual CBC and B12 level

- Chronic disease patients: As directed by your specialist, usually every 3-6 months

- After diagnosis of deficiency: Recheck in 8-12 weeks, then every 6-12 months once stable

Red Flags That Require Urgent Evaluation

Most abnormal MCV results don’t constitute emergencies, but certain patterns concern me greatly:

Rapidly falling MCV with dropping hemoglobin: Suggests active bleeding. I’ve diagnosed GI bleeding, heavy menstrual bleeding, and even occult bleeding this way.

Very high MCV (above 120) with neurological symptoms: Severe B12 deficiency causing spinal cord damage (subacute combined degeneration). This needs immediate treatment.

Abnormal MCV with very low white blood cells or platelets: Could indicate bone marrow failure, leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome. Needs hematology referral.

New macrocytosis in someone with no obvious cause: I rule out serious conditions before attributing it to benign causes.

MCV changes of more than 10-15 points in 6 months: Something significant is happening and needs investigation.

When I Refer to a Hematologist

I’m comfortable managing most causes of abnormal MCV, but certain situations require specialist input:

| Clinical Situation | Why Referral / Further Evaluation Is Needed |

|---|---|

| Suspected thalassemia | Requires genetic counseling and specialized hematology management |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome or other bone marrow disorders | Needs specialist evaluation and possible bone marrow examination |

| Hemolytic anemia (premature red blood cell destruction) | Requires detailed workup to determine underlying cause and specific treatment |

| Refractory anemia (not responding to appropriate treatment) | Suggests an alternative or more complex underlying diagnosis |

| Complex cases with multiple abnormalities | Benefit from specialist assessment and advanced diagnostic testing |

| Need for bone marrow biopsy | Requires hematology referral for procedure and interpretation |

I believe in collaborative care. Hematologists have expertise and tools I don’t, and I’m not too proud to ask for help when my patients need it.

Integration of MCV With Other Lab Values

I never interpret MCV in isolation. Here’s how I use the complete blood count.

MCV Plus RDW (Red Cell Distribution Width)

RDW measures variation in red blood cell size. This combination is powerful:

Low MCV, normal RDW: Think thalassemia. Low MCV, high RDW: Think iron deficiency. High MCV, normal RDW: Think B12/folate deficiency or liver disease. High MCV, high RDW: Mixed deficiencies or early response to treatment

MCV Plus Reticulocyte Count

Reticulocytes are young red blood cells. This tells me if bone marrow is responding:

Low MCV, low reticulocyte count: Bone marrow can’t make cells properly (iron deficiency, thalassemia). Normal/high MCV, low reticulocyte count: Bone marrow suppression or megaloblastic anemia. High reticulocyte count: Active bleeding or hemolysis (cells breaking down, marrow responding by making more)

Peripheral Blood Smear

Sometimes I order a manual blood smear review. The lab technician or pathologist looks at actual red blood cells under a microscope.

Findings I look for:

Microcytic, hypochromic cells: Iron deficiency. Target cells: Thalassemia or liver disease. Hypersegmented neutrophils: B12 or folate deficiency. Schistocytes: Hemolytic anemia. Spherocytes: Hereditary spherocytosis or autoimmune hemolysis

These findings often clinch the diagnosis.

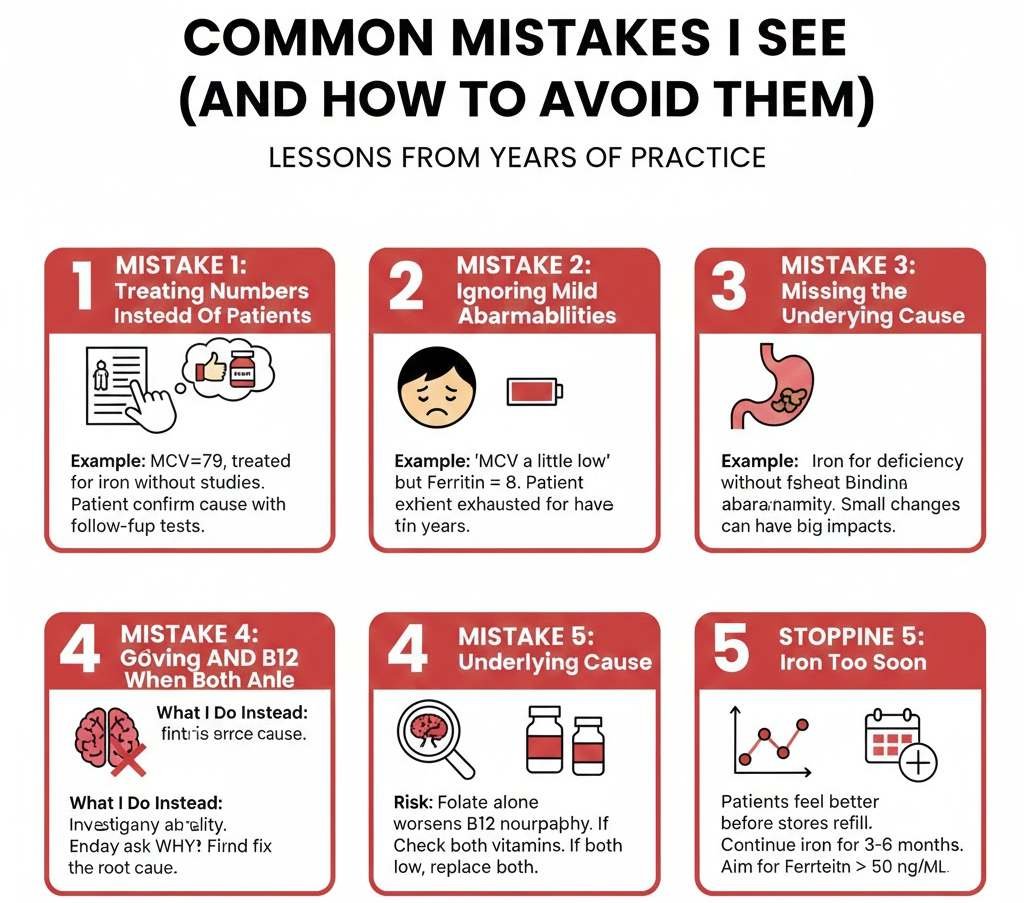

Common Mistakes I See (And How to Avoid Them)

After years of practice and seeing patients from other providers, here are the errors I encounter repeatedly:

Mistake 1: Treating Numbers Instead of Patients

I’ve seen physicians prescribe iron for an MCV of 79 without checking iron studies. The patient had thalassemia and didn’t need any iron supplementation.

What I do instead: Always confirm the cause before treating. Order appropriate follow-up tests.

Mistake 2: Ignoring Mild Abnormalities

“Your MCV is a little low, but it’s not too bad” is something I hear patients report from previous doctors. Then I find a ferritin of 8, and the patient has been exhausted for two years.

What I do instead: Investigate any abnormality, even mild ones. Small changes can have big impacts on how people feel.

Mistake 3: Missing the Underlying Cause

Prescribing iron without finding out why someone is deficient is incomplete care. That colon cancer won’t heal itself.

What I do instead: Always ask why. Why is this patient iron-deficient? Why is this patient B12-deficient? Find and fix the root cause.

Mistake 4: Not Giving Folate AND B12 Together When Both Are Low

Giving only folate when both are deficient can worsen B12 neuropathy.

What I do instead: Always check both vitamins. If both are low, replace both.

Mistake 5: Stopping Iron Too Soon

Patients feel better before their iron stores are fully replenished. They stop taking iron, and symptoms return months later.

What I do instead: Continue iron supplementation for 3-6 months after MCV and hemoglobin normalise to rebuild iron stores. I aim for ferritin above 50-100 ng/mL.

Patient Questions I Answer Regularly

Can I diagnose myself with an online MCV calculator?

No. While online tools can provide information, they can’t replace clinical judgment. I consider your symptoms, medical history, physical exam findings, and other lab values together. Self-diagnosis and self-treatment can be dangerous.

Will taking a multivitamin fix my abnormal MCV?

Maybe, but probably not. Multivitamins contain small amounts of iron, B12, and folate. If you have a significant deficiency, these doses are insufficient. You need targeted, higher-dose supplementation under medical supervision.

How long until my MCV normalises?

It depends on the cause and treatment. With iron supplementation, I typically see improvement within 4-8 weeks and full normalisation within 3-6 months. With B12 injections, improvement starts in 4-8 weeks, and full normalisation can take 3-6 months.

Can stress cause abnormal MCV?

Not directly. Stress doesn’t change red blood cell size. However, stress can worsen underlying conditions or lead to poor dietary habits that contribute to deficiencies.

Should I get genetic testing for thalassemia?

If you have persistent low MCV despite normal iron studies, family history of thalassemia, or ancestry from high-risk regions, then yes. Hemoglobin electrophoresis is the first step, followed by genetic testing if needed.

This matters especially if you’re planning to have children. If both parents carry thalassemia genes, their children are at risk of severe thalassemia major.

MCV Testing and Red Blood Cell Analysis

Medical technology continues to advance, and today you don’t have to wait for a doctor’s appointment to understand your MCV numbers. Use our free MCV blood test calculator below to check your red blood cell size instantly using your lab values:

🔬 MCV Blood Test Calculator

Calculate the Average Size of Your Red Blood Cells

Calculate Your MCV

Your MCV Result

What is MCV?

MCV (Mean Corpuscular Volume) measures the average size of your red blood cells. It helps doctors diagnose different types of anemia and blood disorders.

Normal Range

The normal MCV range is 80-100 femtoliters (fL). Values below 80 indicate small red blood cells, while values above 100 indicate large red blood cells.

Why It Matters

Your red blood cell size can reveal iron deficiency, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, genetic conditions, or other health issues that need attention.

Here's what's on the horizon for MCV testing and red blood cell analysis:

- More sophisticated cell counters: Modern analysers can measure dozens of red blood cell parameters beyond MCV, providing incredibly detailed information.

- Point-of-care testing: Portable devices that provide complete blood counts in minutes, useful in remote areas or emergencies.

- Artificial intelligence interpretation: AI systems that integrate multiple lab values with clinical data to suggest diagnoses. I'm cautiously optimistic about this technology as a decision support tool, but it won't replace clinical judgment.

- Genetic testing becoming routine: As costs decrease, genetic testing for hemoglobinopathies and other blood disorders will become standard care.

My Final Thoughts as a Physician

The MCV is a simple, inexpensive test that provides tremendous diagnostic value. I've diagnosed life-threatening colon cancer, prevented irreversible neurological damage from B12 deficiency, identified genetic conditions, and helped countless patients feel better by optimising their red blood cells.

But here's what I want every patient to understand: your MCV is just one data point. It's valuable, but it needs context. My job is to integrate your MCV with your symptoms, physical exam, other lab values, and medical history to create a complete picture of your health.

Don't ignore abnormal results. Don't self-treat without a proper diagnosis. Do work with a physician who takes your concerns seriously and investigates thoroughly.

Your red blood cells are carrying oxygen to every single cell in your body right now. When they're the wrong size, you feel it, even if you can't quite explain why you're so tired. That fatigue has a cause, and that cause deserves investigation.

Take your health seriously. Ask questions. Advocate for yourself. And remember that optimal health often requires more than just being "within normal range." You deserve to feel your best, not just to have numbers that technically fall within reference ranges.

If you have an abnormal MCV, don't panic, but don't ignore it either. Work with your doctor to find the cause and fix it. Your body is trying to tell you something. Listen to it.